A Good Day to Kodály

May 10, 2017

I spent the spring and summer of 2016 learning the Kodály Sonata and prepping for a recital. These are the program notes which accompanied the recital.

St. Mark’s on the Campus

3 o’clock

A Good Day to Kodály

Jessica Dussault, cellist

Kip Austin, cello

with

Dr. Karen Becker, cellist

“Joe” Charrotte, cello

– Program –

Max Reger (1873 – 1916)

Suite No. 2 in D minor for Violoncello Solo, op 131 (1915)

Präludium

Gavotte

Largo

Gigue

– pause for retuning –

Kodály Zoltán (1882 – 1967)

Sonata in B minor for Solo Cello, op 8 (1915)

Allegro maestoso ma appassionato

Adagio con gran espressione

Allegro molto vivace

Friedrich August Kummer (1797 – 1879)

Three Duets for Two Cellos (1835)

Duet II: Rondo

– Reception with many sorts of cookies to follow –

Many thanks to...

Dr. Karen Becker, for her wisdom in lessons and enthusiasm in duets! Tracy, for teaching me in my youth and for her Kodály coaching. Lily for being willing to pinch hit some mad piano if needed for a duet. St. Mark’s for providing a wonderful space. My parents for baking cookies and setting up the feast and last but certainly not least, Donna for selflessly volunteering to turn pages (and even cover a few notes) for me if I didn’t memorize the Kodály in time.

I have been wanting to play the Kodály Sonata since I first heard it in a studio class at UNL. When I got a little downtime this spring, I thought I would give it a spin. Turns out that the Kodály is….challenging. Knowing that I would never truly attempt to learn the piece unless the fear of God was put in me, I decided to give a recital. Thanks for coming out for an afternoon of cello and for providing me with the motivation to follow through on my goal!

I hope that you enjoy these pieces as much as I have!

Before there was Reger, before there was Kodály, there was J.S. Bach. In the early 18th century, Bach wrote six unaccompanied cello suites which remain widely performed and dearly loved today. For two centuries following Bach’s suites, very few unaccompanied cello pieces were created. This is not to say that no one was writing for cello! The 18th and 19th centuries saw the creation of many amazing concerti, cello-piano sonatas, cello solos with accompaniment, and more, but unaccompanied cello works were the unchallenged domain of Bach.

Then in 1915, in the midst of the Great War, two musicians took up the solo cello cause. In Germany, Max Reger published three suites for solo cello, the second of which appears on this program. At the same time in Austria-Hungary, Kodály Zoltán (surname placed first in Eastern name order) began writing a cello sonata which would not be performed until just before the war’s end in 1918. Despite the similar time in which they were written, the two pieces are dramatically different, something which is apparent even from the first notes.

As a musician, Max Reger wore many hats including concert pianist, church music director, conductor, composer, and educator. In a bid to have one of the coolest sounding resumés, he was even the Hofkapellmeister (music director) at the court of the Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen in the German Empire. Reger looked to the rich tradition of western high art music for inspiration and many of his pieces reflect form and style choices of earlier eras, like the baroque and classical. Indeed, compared to composers active at the time (such as Debussy and Stravinsky), Reger’s cello suites strike a very traditional chord. We will never know how his writing might have evolved during his later life, for he died suddenly at the age of 43 only a year after publishing the cello suites.

Kodály, too, looked to the past for inspiration. However, as an ethnomusicologist, Kodály was intrigued by Hungarian folk songs. Kodály and his friend, Béla Bartók, travelled across the country creating phonographic recordings of traditional instruments, melodies, and lyrics. Kodály’s passion about folksongs is incorporated into much of his music. Like Reger, Kodály also was an educator. His ideas evolved into a pedagogical concept called the Kodály Method. Kodály attempted to introduce proposals for music education to the Hungarian Soviet Republic, one of several short-lived governments following the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. However, it would be several decades before the Kodály Method gained traction internationally. Unlike Reger, Kodály lived to the age of 84.

As far as I know, Kodály and Reger never crossed paths, but Reger’s works were known in Hungary and were apparently not well received by our ethnomusicologist friends Bartók and Kodály. Kodály wrote that he had no interest in reading Reger’s cello suites and Bartók surely had Reger’s recently published cello suites in mind when writing of Kodály’s cello sonata: "No other composer has written music that is at all similar to this type of work—least of all Reger, with his pale imitations of Bach." Reger didn’t have an opportunity to respond, but I imagine he would have had something to say about it. Reger once wrote to a critic: "I am in the smallest room of the house. I have your review in front of me. Soon it will be behind me."

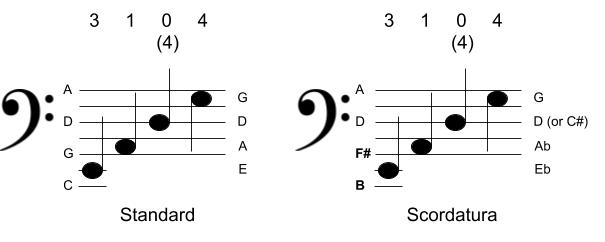

One note of interest about the Kodály Sonata is the cello’s tuning. The piece is “scordatura,” specifying that the two lowest strings of the cello be adjusted down a half step from G and C to F# and B, respectively. The music is notated as though the strings had not been tuned differently, which makes things a little trippy when learning the piece. In the below chart on the left, the cellist plays the notes with their 3rd finger, then 1st, open string, and 4th finger. They could optionally play the open string with a finger on a lower string and it would result in the same pitch (D) in standard tuning.

On the right, the G and C strings have been adjusted down. However, the cellist should just pretend that everything is normal and place the same fingers as before. Now, the resulting pitches are different. In the scordatura example, the option to switch strings on the third note matters, as the D string is still tuned to "D" but the lower strings are tuned down! Scordatura may seem novel, but actually the technique was not new during Kodály’s time – in fact, J.S. Bach even used it for one of his cello suites in the 1700s! Who’s imitating Bach, now, Bartók?!

Having tuned down for the Kodály, I’ll be tuning right back up to join Dr. Karen Becker in playing one of F.A. Kummer’s beloved cello duets. Kummer was a 19th century cellist based in Dresden, preceding Kodály and Reger by several decades. Widely known for his talents, he was the sort of player who could casually mention that he and Franz Schubert had given a chamber recital which Robert Schumann happened to attend (and that’s just an average Tuesday evening). A pedagogue as well as a superb player, Kummer published the Violoncello Method in 1839, which remains a popular resource today. I recall practicing string crossings out of that volume when I was in middle school!

Speaking of Kummer and middle school, I’d like to mention that the last time I played a Kummer duet was in 8th grade with my friend Sarah Bailey. We liked Kummer’s duets so much that our “band” Combustible Clover played a summer tour (a church service) and dropped an album (with a word art cover and everything) featuring the first duet.